W3 Company - 'Voices from Vietnam' |

|

Whisky 3 Company, 6RAR/NZ (ANZAC) and 2RAR/NZ (ANZAC), 1969-70 The CSM’s Business The wily Sergeant Major’s head twitched, then, with a slight adjustment to his floppy bush hat across his eyes, turned slowly in the direction of the familiar ‘thud, thud…’ sound away off in the distance. He could tell that the noise was not from mortar or artillery fire. It was obviously the distinctive cry of the green-crested Huey… his groceries were on the way. He estimated the chopper would be on his pad inside eight minutes; he would have to get his team cracking. He rolled leisurely out of his hoochie gathering his gear as he went. The CSM then hissed quietly to the four lads from Company HQ who were to give him a hand and led them off in single file to the edge of the clearing that they had marked with a bright orange panel a half-hour or so before. He knelt down on one knee and propped himself up on his M16. With quick hand signals he pointed the troops to their posts around the pad and scanned the bush line once more for any danger signs. He saw none. The thudding of the Huey came closer and closer.

Once the helicopter came into view across the tree tops, the CSM leaned

forward and rolled a smoke canister into the centre of the clearing. It

took just a few seconds for a wisp of bright yellow smoke to stream slowly

from the container. At that point he nudged his signaller, who immediately

reported ‘smoke thrown, over’ in the air support radio net tha ‘Kii…wi… 58A, this is …ahhh… Al…ba…tross… 06, I see ye…llow, o…ver.’ ‘Albatross 06, Kiwi 58A, correct, over.’ ‘Zzzzzzzzt… we’re… on our… way in aahhhh… out.’ By this time, the pad was shrouded in a yellow fog. The CSM moved out to the centre of the landing area and faced the approaching chopper. He slowly raised his two shirt-sleeved arms in the air, the palms of his hands facing outwards. This was the bit of his job that WO2 Doug Mackintosh did not relish. He had done it hundreds of times in the past nine months on W3 operations, but it made him feel vulnerable and uneasy. There he was, stuck out in the open like a shag on a rock, brightly coloured smoke billowing high into the air with a huge shuddering green beacon hovering directly above, seemingly signalling to every VC in the parish his exact location. Smoke swirled away as the chopper descended, then, before the machine entered in-ground-effect hover, a wild up draught picked up dust, twigs, small stones and insects and flung them around the man on the pad. Bits of debris flew up his nose, became lodged in the cracks around his squinting eyes and stuck in his ears and hair. Then there was a quieter moment, like it would standing in the eye of a hurricane, as the helicopter settled into a hover just a metre off the ground. This was the time to unload. He motioned his team in from the ten o’clock and two o’clock positions from the nose of the Huey and they gathered below the skids as the crew tossed out their resupply packages. Four clean bodies also leapt out and the CSM marshalled them away from the aircraft and into the tree line. One of the troops crouched under the chopper gave the CSM the thumbs-up that everything was unloaded and he, in turn, relayed that signal to the pilot. The power of the turbine engine came on again, the nose dipped, everyone on the ground ducked in the hail of flying debris as the helicopter exited the pad. All was quiet in the jungle again… except for the fading ‘thud, thud…’ of the rotor blades and the cherry message on the radio from the aircrew as they returned to their refrigerated beer, hot showers and flush toilets. Meanwhile, the Sergeant Major led his dusty, sweaty, smelly men back to warm foul-tasting water, a cold wash from a mess tin and a lavatory dug with an entrenching tool in the soggy soil. This resupply routine played an important part in the CSM’s existence within a rifle company in Vietnam. His place of work was within the bounds of Company HQ alongside the Officer Commanding (OC). Doug Mackintosh was good at his job and he enjoyed it immensely. It gave him great satisfaction every two or three days to see his collated maintenance demand (maintdem) message return to him as a successful resupply run. He made the system work. As long as it ticked over nicely and the ammo, rations, water, mail, medical stores, replacement clothing and weapons came through on time, the company remained a fully effective fighting machine. It may not have been a glamorous role for an experienced professional soldier (he rarely saw his own troops out in the platoons, let alone the enemy on operations), but he knew full well his part in the running of the company was vital. The High Road to a Warrant Doug Mackintosh was 35 years old and sixteen years into a long army career when he became the master provider for W3 in 1969. He was ideally suited to the job although he had never received any special training for it. His credentials had been earned the hard way – through the long route march of army experience and from being on the receiving end of both efficient sand abysmal resupply service down through the years. He knew instinctively how poor resupply could destroy a units morale, and how reliable service could lift it.

Right from his earliest beginnings, Doug came to know and understand the

Army. He was born in Eton Township in England, virtually under the walls of

Windsor Castle. As a small boy, he had seen the ramrod straight figures of

the guardsmen of the royal household regularly on duty at Windsor. His

father had been a soldier in both World Wars and had been away fighting

during Doug’s early boyhood. Doug had begun a career as a police cadet in

the UK after leaving school, but his parents decided to emigrate to New

Zealand. He spent his eighteenth birthday on board a ship crossing the

Tasman Sea in 1953. Two days later, on his very first day in Christchurch,

he presented himself to the Area Recruiting Officer to volunteer for

Compulsory Military Training (CMT). He completed his initial training,

transferred to the Regular Force (RF) as an infantryman, then passed his

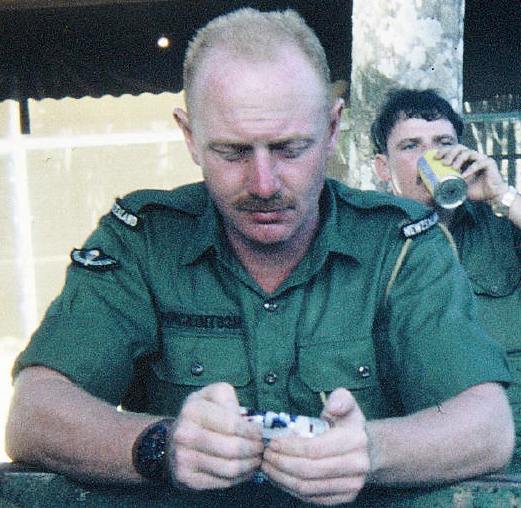

instructors course. Private Mackintosh’s enlistment was somewhat timely for him, because it coincided with the formation of the first NZSAS unit. He volunteered with 39 other soldiers from Burnham Camp, passed the medical and was accepted. He trained for six months in Waiouru as a Lance Corporal with 4 Troop. His unit was then posted to active service in the Malayan Emergency for two years. Our squadron of 120 men spent most of its time in the bush. We operated in patrols of five or six and we became very proficient at what we did. I was quite often appointed patrol leader or otherwise served as 2ic to the officer or senior NCO. It was an excellent introduction to my service career. I could not have asked for anything better. We were taught to aim for the very top-end of achievement, to accept nothing less. ‘Nothing is impossible’’, so we were taught. That motto and all the lessons I learned as an 18-19 year old stayed with me throughout my career. NZSAS patrol in Malaya 1955 His time immediately after his SAS tour of duty was spent training in a more extensive range of infantry skills. But Doug Mackintosh then embarked on a progression of postings that enabled him to refine his craft and his thinking about infantry warfare and to move through the NCO ranks at a fairly swift rate. He served in 2 New Zealand Regiment in Malaya, as platoon sergeant of 9 Platoon, C Company, and he eventually became platoon commander for six months. He was selected to serve at the Jungle Warfare School in Kota Tingi, after which he became intelligence sergeant until the end of his battalion tour. After a period back in New Zealand, he was reassigned to Malaysia as the battalion Signals Platoon Sergeant. His practical experience in the first twelve years of his career earned him an appointment at the School of Infantry where he was promoted to Warrant Officer in charge of the Tactics Wing, and then the Support Weapons Wing. In just a dozen short years, WO2 Mackintosh had done just about everything he could have done to develop into a most accomplished professional infantryman in the battalion environment. He understood almost all the elements that made a battalion an effective fighting force. He knew about training, discipline, morale, intelligence, communications, patrolling, weaponry, minor tactics, survival, jungle navigation, command and logistics. His knowledge of all these elements was gained largely through practical experience. So, it was not really a surprise, when, having made his request to serve in Vietnam known, he was called forward by Major Evan Torrance, the new commander of W3 Company to be his CSM.

School of Infantry 1967 - Junior NCO Minor Tactics Course, WO II Mackintosh centre front row The Black Band He was the last man to join the W3 team, but Doug Mackintosh was not one to feel left out. Malaysia was not strange to him since the garrison had been his home on three previous occasions. He also had at least six months to serve with his new unit before they would deploy as W3 to Vietnam. The deployment date was to be November 1969, and W3 would replace W2 as the fifth rifle company of 6RAR/NZ (ANZAC). The Australian component of the battalion would be six months through their one-year tour by the time W3 arrived, but that prospect did not seem to daunt the Kiwis at all. Whisky companies had already established a fine reputation in Vietnam and W3 was determined to excel in their turn. They trained hard in Malaysia and were as ready as they would ever be, come November, tactically, technically, and in terms of morale. The Company seemed keen to make its mark, and Doug Mackintosh recalled an unusual measure that was taken in the weeks leading up to deployment: For some unknown reason W3 personnel began to wear black badges of rank on their uniforms. This was quite a unique move on the company’s part and I could not find any regulation that might forbid the practice. Everyone else wore white rank badges in the tropics. Black seemed a sensible measure if NCO’s and officers opted to wear rank in the bush, but the only reason W3 adopted it seemed to be to enhance company spirit. I convinced the local tailor to sew black rank on all the junior NCO’s uniforms and, by the time we got to our farewell parade in November, everyone was wearing it. I even had my warrant officer’s wrist badge painted black and I wore that on parade.1

1. W3 continued with this dress distinction through its Vietnam tour and was informed by the CO of the battalion in Singapore, where they were posted after Vietnam, that the company could continue the practice there. Coincidentally, the second Australian battalion W3 served with in Vietnam, 2RAR, wore a black lanyard so their Kiwi cousins wore that with pride as well. The CSM sensed certain nervousness about the Company when it arrived in Vietnam. There were some secretly held doubts about whether they would do things properly and whether they had prepared fully. It did not take long for him to realise that these fears were unfounded. In the induction training provided by the Australian battalion, the Kiwis found they had nothing really new to learn. There was some confusion about the proper way to set out and arm claymores, and there was a new evacuation stretcher in use for jungle extraction by helicopter winch. But they were probably the only two issues. In the Bush With the CSM buried deep inside the perimeter in the Company HQ sector, he was not likely to see much action out where it was all happening, with the platoons. Nevertheless, the experienced Sergeant Major had real responsibility in the melding together of the 22 or so disparate individuals who formed the Company Headquarters. He had to construct an extra ‘platoon’, and coordinate the actions of a group made up of a range of different skills, from padres to medics and engineer mine clearing teams, any of whom might be attached to the Company from time to time. There were a couple of occasions during the twelve month tour when the OC let him loose in the jungle from the HQ area to conduct clearing patrols, but mostly he was locked into running the Company HQ or the maintdem-resupply cycle. On one occasion, he was taking a patrol drawn from members of the support section in Company HQ on a sweep around the HQ area to confirm they were secure. The patrol encountered some heavy going in a section of jungle that had been turned over by B-52 bombing runs. There were no tracks. Trees had been cut into jagged stumps, twisted branches and splinters and debris covered the ground. The patrol snaked its way through this maze at a very slow pace. The patrol leader stopped suddenly and put his hand to his ear, they could all hear voices, voices speaking in Vietnamese. They were in a no-go area for local people, which meant that anyone caught inside the zone could be presumed to be enemy. But, because of the terrain, the Kiwis could not see anything over the smashed up foliage. They could only hear voices. The sounds were nearby, within 20 metres, and moving across the patrols front, left to right. As the patrol commander, Doug was in a pickle. He could not engage the supposed enemy with aimed shots; nor was mortar or artillery fire an option for him. One choice he did have, was to throw grenades over the fallen trees in the hope of killing a few of the enemy. But he decided against that, and eventually led his patrol around the obstacle and onto the trail used by the group they had heard. They followed for a while, but never caught up with the party. The episode haunted the Sergeant Major for a long time afterwards. He felt he had been denied a battle victory of sorts over the VC. In time he came to realise that perhaps it been for the best. One of the major principles to be observed, whether hunting man or beast he recalled, was that you should positively identify your target. Knowing the poor people of the Vietnamese villages at the time, the group the patrol heard might well have been civilian villagers foraging for firewood, as they often did. He was glad, in the end, that he did not throw grenades at voices. …and into the Fray In December of 1969, W3 conducted the only company level attack of their tour. The majority of contacts with the enemy had been platoon-sized affairs, so a company action was quite exceptional. Late one afternoon, as the whole company was moving through an area, one of the platoons propped and went to ground at the sound of a large number voice ahead of them. A short recce patrol confirmed there were about 30 enemy troops in a temporary camp. Luckily, the whole company was within two hour march of the position, so it was decided to carry out a full company assault. Quietly and swiftly, the whole company closed up onto the enemy’s position. Plans were made, the Task Force HQ was alerted, and artillery was organised to bring fire down on the network of likely VC escape routes. Everything was tied up by 1900 hours. The Kiwi company settled down for the night readying themselves to attack at dawn. From his rearward position in the HQ Group, CSM Mackintosh watched all the action develop and listened intently to the radio nets. He was intrigued that the primary source of fire support for the attack would come from the sub-units own machine guns (M60) firing en masse. The machine gunners linked three standard 80-round belts together and the intention was to open the assault with a salvo of four weapons, each firing 240 rounds into the known enemy bivouac area non-stop. He remarked that no one really knew if the M60 was even capable of that rate of sustained fire, but they were prepared to have a go. At a range of only 30 metres, this amount of firepower should have inflicted serious casualties among the enemy even before the charge came from the platoons going in on foot. The idea was that the sudden shock attack and the heavy firepower would make the enemy scatter and run to their deaths along the escape routes, filled by then with artillery fire, In the event, the Company could only claim one kill; that of an unfortunate VC who had left the inner position to attend to his morning ablutions. The remaining 24 survived the M60 firing, unscathed; their position had been in a saucer shaped depression in the ground and most of the rounds had gone over their heads. They all ran for it before the infantry arrived. But, even then, luck was on the VC side that day. As the OC called for the artillery blocking fire he was told ‘sorry, we cannot fire, we do not have air clearance’. Not one artillery round was fired. 24 of the 25 enemy party escaped. W3 took one enemy killed and 25 packs that had been left behind in the hasty evacuation. The CSM thought he might have had a chance to save the day for the Kiwis when he managed to contact a US Army helicopter gunship in the area. The gunship flew in and hit the suspected escape routes with 40mm mini-gun bursts but there were no confirmed casualties from that action to add to the tally. Doug was very impressed with the US response and their willingness to participate spontaneously. Statistics off the Scoreboard The Company Sergeant Major, as the senior non-commissioned officer in the sub-unit, is usually in a position to sense the mood of the rank and file. He is the one who deals with the disciplinary issues, who attends to serious issues of soldiers’ welfare and who can measure activity, successes and failures. Doug Mackintosh was no exception in his role as CSM of W3. At the end of the company’s tour of duty, he looked back and reviewed in his own mind just how successful they had been. His assessment was that, while in some areas they could have done better, on the whole W3 was a fine outfit and it had done its job well. He had a minimum of disciplinary issues to deal with and absolutely none that arose from any incident on combat operations. If you were to ask him ‘How good was W3’, he would paraphrase, firstly, the quote from an infantry training pamphlet at the School of Infantry that defined the role of the infantry in battle: ‘to close with, and kill, the enemy on the ground, in all weather, by day or night… etc, while sustaining minimal losses of one’s own force’ (or words to that effect). Therefore, he would argue that excellence of performance must be measured in those terms. In the case of W3, in comparison with the other companies in the battalion, he examined the battle statistics for the year and found:

In the CSM’s estimation, the statistics reveal that W3 lost one man for every 18 enemy killed while, on average, each of the other companies in the battalion lost one man for four enemy killed. Career Achievements After Vietnam, Doug Mackintosh served on in the Army for another eighteen years. He reached the pinnacle of any non-commissioned soldier’s career, the rank of Warrant Officer Class 1, as soon as his company (W3) had reached Singapore and disbanded. He was made acting Regimental Sergeant Major (RSM) of the battalion in Singapore, where he found it difficult to adjust to peacetime duties and the non-operational attitude that prevailed there. He was aghast to discover that the garrison did not hold sufficient ammunition in its magazines for the battalion to ‘fight its way out the front gate', as he put it. Furthermore, he became disturbed that the Singapore battalion was training for exercises rather than training for war. For a combat-hardened old soldier these things were hard to accept. He returned to New Zealand and continued RSM duties with the RF battalion in Burnham for a year before making a complete change and assuming the RSM’s role for the territorial force (TF) battalion in Dunedin, the 4th Battalion, (Otago and Southland) Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment. Even though he enjoyed the challenge of making training interesting for soldiers in a TF environment, his time in the south, including a posting as the Area Warrant Officer, eventually could not stimulate him enough and he became bored. His cure for boredom was to apply for, and take, an officers commission as Lieutenant and Quartermaster in the infantry. This slight elevation in rank status gave Doug the chance to make a difference to the lives and careers of his soldiers. In staff appointments in HQ Home Command and Army General Staff in Wellington, he was responsible for planning and implementation of training and for what is now called ‘human resources management’ for warrant officers and NCO’s. In the latter role, he did not merely sit behind his desk in Wellington and make arbitrary decisions on soldiers’ futures, he insisted on travelling to camps and bases to talk to soldiers about their preferences and personal circumstances. He was able to discover and implement what was best for the soldier and best for the Army. His career ended, as it had begun, in the South Island. He took a terminal posting to Nelson for five years, during which time he administered army affairs in the province and commanded a company of TF soldiers. He enjoyed his time with the TF once more and was encouraged by the attitude of the young part-time soldiers to whom he was able to impart his own service philosophy ‘Nothing is Impossible’. He found them willing to take on the most difficult challenges and to succeed. In their success he found his reward (as he had in the achievements of all his soldiers over his 35-year career). Doug Mackintosh eventually retired with his wife to Christchurch where he finds more of life’s rewards in keeping his garden in regimental order and in marching his dog daily at light infantry pace. |

t

the CSM’s party always tended. Down through the earpiece of the plastic

handset of the 25 set came a cackle, then the tremolo voice of the pilot:

t

the CSM’s party always tended. Down through the earpiece of the plastic

handset of the 25 set came a cackle, then the tremolo voice of the pilot: