|

CHAPTER

6: OLD SALT AND SUPER GLUE CHAPTER

6: OLD SALT AND SUPER GLUE

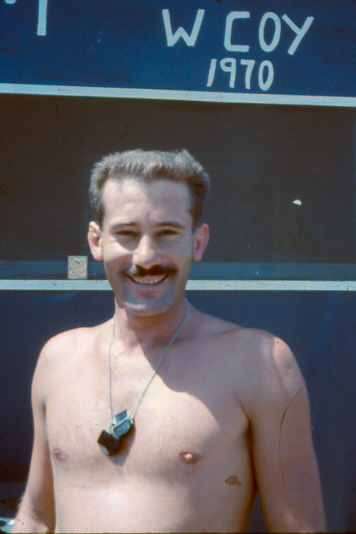

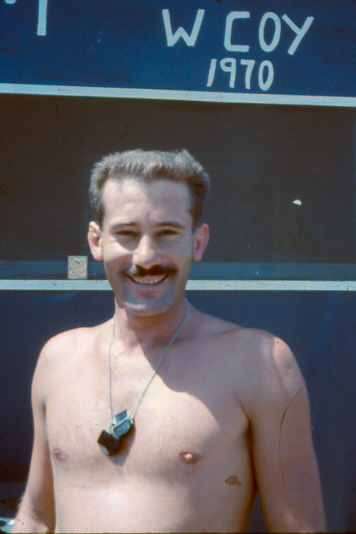

804520 Sergeant Denny KING,

RNZIR

1

Platoon, Whisky 3 Company

1969-70

Getting

Some Time Up

The platoon sergeant in

Vietnam was the ‘old hand’, the backbone of the team.

He was the senior soldier and usually the most experienced

in the platoon. He was like the glue that held the

whole thing together. I don’t mean to boast by saying

those things, but platoon commanders were often only about a

year out of their respective training establishments and

lacked the years of experience I had accumulated one way or

another and most of the soldiers had only been in the army

two or three years on average. Whereas the platoon

sergeants, like me, had done their time in the ranks, had

been section commanders, and had at least ten to twelve

years’ service behind them. Most of the sergeants in

Vietnam also had operational experience in Malaya and

Borneo.

Sergeant Denny

King’s claim to ‘old hand’ status was backed up by a service

career that began in 1960 in Hokitika on New Zealand’s West

Coast. He had been a candidate for army service two years

before, when he would have been due to be called up for

Compulsory Military Training (CMT). But, the second Labour

Government disbanded the national service scheme as part of its

election manifesto. Denis King was born in 1940 and saw

his father head off with 2NZEF for the Italian campaign in 1943.

He had a brother, Don, in the Navy and another, David, in the

Territorial Force (TF) as Company Sergeant Major (CSM) of the

local sub-unit in the late 1950's. His brief experience in

civilian employment just did not prove exciting enough, so he

enlisted in the army's regular force as soon as he was old

enough.

Within his first two years of service Denny completed his basic

and corps training and an instructor’s course. He was

promoted to Lance Corporal and was a section commander in

1961-62 with with what was then known as LTCOL Les Pearce’s

Battalion in Malaya. He found the training regime, which Pearce

and his senior staff had modelled on General Freyberg’s World

War II divisional training ideas, strenuous but rewarding

1.

The unit trained non-stop. Other units would go on leave;

but the Battalion would be either in the bush working on their

jungle training or participating in organised sports events.

They were fit too. The Kiwi Battalion won every sports

event going, rugby, tug ’o war, swimming…the lot. The

competition between them and their Australian and British rivals

was fierce. In Malaya the then CPL King contracted a severe

illness, acne vulgaris, which was to complicate his service in

South East Asia for many years. The condition was

exacerbated by carrying a heavy infantryman's pack, continual

perspiration in the tropical climate, wearing wet and dirty

clothing and not being able to to regularly wash the effected

area. He was repatriated in 1962 with a temporary medical

downgrade. The condition turned out to be worse than

anticipated and it took him five years, until 1967, to get back

up to full fitness.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 2NZEF

veterans included the Battalion 2ic and most Company Commanders,

the RSM, some CSM's and platoon sergeants. A large number of

veterans who had served in 'J' Force, 'K' Force and the Malayan

Emergency were also placed in training and leadership

appointments.

His journey back to a completely healthy state was certainly a

drawn out affair. He had to struggle to convince the

authorities that he could take his place in a combat unit again.

He used his love of sport as a means to reach peak fitness and

to show the Army why he should be medically regraded to

operational standard. He served as the cadre NCO in

Blenheim with the 2nd Battalion (The Canterbury, Nelson,

Marlborough, West Coast) Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment's

TF Company. Sergeant King played representative rugby for

Marlborough and Combined Services in his time there. The

highlights for him were taking the field against the 1965

Springboks and the 1966 Lions.

2

After that, the Army had to upgrade him and move him out of the

wilderness after five years.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

2 Denny

King played for the Combined Unions Marlborough – Nelson –Golden

Bay – Motueka as a loose forward against these overseas teams.

The Combined teams lost both games: 6 – 45 vs. the 1965

Springboks and 14 – 22 vs. the 1966 Lions.

He became a Four-Star Instructor at the Battalion Depot in

Burnham in 1967-68 under the unit's Training Officer Warrant

Officer Class I Roly Manning (a former member of 1NZ

Regiment1961-63. King was part of a special training team

that Manning had assembled (predominantly NCOs' from 1 NZ

Regiment 1961-63) to prepare soldiers and NCOs for operations

overseas. In November 1968 Sergeant King was posted back

to Terendak Garrison in Malaysia with his family – he had

married Jeanette, a childhood sweetheart from the Coast in 1963.

They had two children by the time King was called forward to

serve in Vietnam in 1969.

It was the intense training programme that the Kiwi infantry

units in Burnham and Malaysia went through that best equipped

Denny King to become a knowledgeable and experienced NCO.

His personal training and preparation for Vietnam was enhanced

in the training units by being able to rub shoulders with

veterans of the early companies that had deployed to Vietnam by

the end of 1968.

I was able to benefit

greatly by this contact with these experienced soldiers.

I took every opportunity to pick their brains on all kinds

of subjects and down to the finest detail. I would ask

them what operational issues were different in Vietnam from

what we had done in Malaya back in 1961-62. For

example, I learned that while personal weapons had to be

meticulously cleaned in Vietnam, they should not be

over-oiled because of the dusty conditions in the dry

season. I also discovered a shift-up in the size of

operational organisation that the infantry would run in the

field. In Malaya the basic organisation was

undoubtedly the section; small six to ten man patrols formed

the best fighting package to take on the CT (Communist

Terrorists). We learned that, in Vietnam, the optimum size

had become the platoon operating within a fully deployed

company. The contact reports and after-action

summaries that we received from the units in Vietnam told us

this sort of thing. So that is how we structured our

training.

On his return to Malaysia in 1968, and during the frequent

training exercises he was involved in, his acne condition

returned. He realised that he required assistance to

manage the condition, and needed something to keep the pores of

his skin unclogged. Largely on his own initiative, he

acquired a container of solution, similar to liquid soap, and

with assistance from his radio operator, applied this regularly

to the affected area. This regular washing routine

continued ion Vietnam, and was successful in keeping the

condition under control.

Before he arrived in Vietnam with Whiskey 3 Company (W3),

Sergeant King had reached some important decisions about his

role. Because of his length of service and experience in the

ways of the army, and because he had received all the training

in operational skills at the tactical level, he felt that he had

to accept some responsibility for leadership of those junior to

him in rank and to provide unstinting support for the commanders

more senior to himself. In the platoon setting he saw

himself as the glue that held it all together. He was

responsible for mixing and setting the resin that was composed

of four interconnected elements:

Morale, standards and discipline

As platoon sergeant I

was well placed to sense and react to the feelings and moods

of the troops. We could lay down the standards of

behaviour and job performance expected of the members of the

platoon, but it was up to the individual soldiers themselves

to take ownership of their special role and to do it to the

best of their ability. It was not so much a matter of

discipline within the platoon but one of self-discipline on

the part of each person. I did not have to do much to

monitor the behaviour or performance because they knew when

things were not going right and their mates certainly told

them. But I had to make sure there was back up for any

individual in case he was taken out of action. So we

crossed trained all members of the sections to do each

other’s jobs as well. To keep morale, standards and

discipline at high levels all we had to do was to encourage

soldiers to be mature, to learn and to make every day’s

performance better than the one before.

Security of the Platoon.

On

operations, especially when we were in contact with the

enemy, my role was always to keep an eye on things from the

rear and to watch our tail. The platoon commander,

quite rightly, was usually concerned with what was going on

up front and with other things like fire support. But

I was always alert to the fact that the most dangerous time

for the platoon was in the aftermath of contact with the

enemy; when there was a tendency for soldiers to let their

attention stray towards the sound of action rather than pay

attention to their own responsibilities. With

adrenalin levels running high we were most prone to lapses

in security; it was my task to ensure that those lapses did

not occur. My approach was to ensure we consolidated

our position first then moved back to the normal routine

gradually. I was usually on to people all the time.

I made sure they checked their weapons, and that they were

aware of the situation around them. I would usually be

in charge of conducting the sweep to secure our position

after any contact. That usually involved collecting

bodies, seeing to the wounded and gathering up prisoners,

captured equipment and documents. This was a dangerous time

and the platoon commander and I carefully coordinated what

was going on. Sentries had to be posted, claymore

mines rearmed and every single soldier had to know what was

going on.

Logistics and

Administration.

If the

platoon ever ran out of resources with which to fight, we

were going to be defeated in battle. It was my job to

ensure that the resupply system ran like clockwork on its

three to five day cycle. So I ordered ammunition,

rations, water and equipment, as they were required. I

simply consolidated the demands from the sections and sent

them along to the company sergeant major (CSM) at company

HQ. I then had to distribute the supplies once they

had been delivered. I had to arrange the evacuation

and replacement of manpower. Some men would depart for

and return from leave, others would need medical attention.

Then, there were things like mail, fresh rations and small

luxuries (clean clothes, cigarettes, toiletries, etc) that

helped keep the troops happy in the field. Our system

worked like a charm and its success was largely due to the

reliability and efficiency of air transport services.

We had the freedom of the skies in Vietnam and the

maintenance demand (maintdem), operational demand (opdem)

and casualty evacuation (casevac) services were used to

maximum effect. It was the urgent deliveries that were

most critical and the high standard of service never

wavered. If we lost a radio in a contact a helicopter

would appear over the trees and a new one would be lowered

onto the smoke marker. We could not have asked for

better.

Battle Second in Command

(2IC).

Above

all else, as platoon sergeant, I had to be ready to step in

to command the platoon should anything untoward happen to

the platoon commander (the boss). I felt the weight of

this responsibility greatly because, to be able to take his

place effectively, I really needed to be aware of everything

he thought, saw and did. I maintained my awareness by

backing him up continually; I was part of the navigation

checking team so I always knew where we were. I

attended all the O (orders) groups so I knew what he had

told the sections and the mortar fire controller.

After he had sited the guns and claymores in defensive

positions, it was my job to check every one and to look

after the detail. The personal and professional

relationship between the Lieutenant and me, the sergeant,

was critical. I was fortunate indeed to have

cultivated a sound relationship with Lieutenant (LT) (Bill)

Blair from the outset. When he joined our platoon in

Malaysia he accepted my request not to make any changes for

a three-month period after assuming command; he looked,

evaluated and decided in full consultation with me.

That was a successful process for all of us. To his

credit he delegated me certain responsibilities and kept me

up to date so that I could take up the reins if required.

A Successful Mix

After the first contact that the platoon had in Vietnam, any

fears that Sergeant King might have held for the capabilities of

the company to which he belonged were dispelled. The

toughness of the competitive training in Malaysia and the

programme of inspired self-discipline all seemed to have paid

off. The platoon’s (and W3 Company’s) efforts were

rewarded in the best possible way; by the receipt of glowing

praise from their Australian Commanding Officer. His words

to the W3 Company Commander during an after-action wash-up were

relayed to the troops. He had said ‘ Well done, Major. The

standard of your soldiers in W3 is at the level that my soldiers

achieved after six months on operations. You have arrived

at that point’. These comments boosted the morale of No 1

Platoon and the members continued to strive for perfection.

Denny King noted some key indicators of excellence of their

performance in the facts that:

The platoon lost

not one soldier killed in action throughout the tour of

duty.

Soldiers’ personal discipline in health and hygiene procedures held up

well; No 1 Platoon suffered no casualties from malaria or

tinea pedis infections,

Platoon members continued to help each other out; some would volunteer to

relieve their mates of sentry duty on the Nui Dat perimeter,

others would share their water selflessly when supplies ran

low,

Any arguments, disagreements or unpleasantness were resolved in-house,

There were no offences within the unit related to the use of drugs,

There was only one accidental discharge of a weapon and that occurred

off-patrol and in a base area, and

Soldiers learned not to repeat mistakes that might endanger themselves or

their mates. (On one occasion in contact with the

enemy a section member threw a grenade in the direction of

the enemy in a heavily wooded area. The grenade bounced off

a tree and returned to the thrower’s position wounding one

soldier in the explosion. There were few, if any, grenades

thrown after that.)

After seven months as platoon commander 1 Platoon,

Lieutenant (LT) Blair was promoted to Captain and became W3

Coy 2ic and was replaced by LT Jim Cutler. The

outstanding leadership that Bill Blair displayed during his

tenure in charge was going to make it difficult for his

successor to continue at such a high level. The

platoon NCO's, realized that they still had a job to do for

a further five months and they had to maintain the same

level of professionalism that they had established.

They decided that they would have to work harder in their

respective roles whilst LT Cutler was coming to grips with

the complexities of being the boss of everything that

happens in a platoon on operations! To the credit of

all concerned everyone accepted the challenge and the

platoon performed well for the remainder of the tour.

At the completion of the tour of duty, W3 Company received

four gallantry awards for their service in Vietnam.

That two of the four awards went to 1 Platoon seemed just

reward for the members.

A Platoon

Sergeant’s View of a Contact with Charlie

The middle of the afternoon was a hot, sticky time of the day in

a Vietnamese jungle. Denny King sat out of the sun under

his half-shelter. He sipped his newly brewed tea from his

aluminium mug with the usual tentative kisses blown onto the rim

with a bottom lip scarred from previous scolding's. Even

brewing tea had a tactical dimension to it for the ever-alert

platoon sergeant; he had stirred the tea with a plastic spoon so

it would not rattle on the side of the mug and break the vow of

silence that the platoon maintained. The humidity did not deter

nature’s creatures from their routine pursuits. He

carefully eyed a patrol of red ants marching like storm troopers

up the trunk of a tree and hoped they would not mass for an

attack on his cosy spot. He had already shooed off a

banded crate and a scorpion that had gatecrashed his picnic.

He was trying to complete his maintdem signal in his green field

notebook. It was a peaceful moment and he was able to

reflect on the fact that after five weeks in the jungle on

operations they had yet to experience any contact with the

enemy. Had they all left the area?

Mid-afternoon was not known as a time for serious engagements

with the enemy. But then, that is the fog of war in

action; the enemy will turn up when least expected. As

guardian of platoon security Denny was confident that their

position was safe enough from intrusion. Preparations for

the night were well advanced. The platoon ambush had been

set at the junction of two streams; Mr Blair had marked out the

gun pits and support positions and Denny had followed up with

his usual checks of the fine points. The troops were keen

and awake to the chance of a contact that evening.

It was at this point that things started to go wrong. One

of the platoon sentries had reported that some soldiers from

Company Headquarters (attached to No 1 Platoon for the time

being) had gone outside the perimeter and down the hill to fill

their water bottles. This was an absolute No! No!

The platoon commander went to fetch them back and Sergeant King

quickly warned the other soldiers what was going on. To be

outside a platoon perimeter in Vietnam was extremely dangerous

and some soldiers had already learned that lesson the hard way.

Things began to happen very quickly. LT Blair had reached

the spot where the errant water gatherers were and was

frantically trying to attract their attention, (as quietly as

possible). However, it was too late. To his dismay

he realised three enemy soldiers, armed with AK47s were entering

the water from the other bank. The enemy had noticed the

two soldiers with their water bottles and were set to open fire.

The sharp crack of rifle fire split the silence that the platoon

had lived with for five weeks. Fortunately, the fire was

from 1 Platoon's sentries who had spotted the the enemy and had

been tracking them for the last few minutes. Two enemy

were felled in the initial opening burst. A third enemy

soldier was hit but disappeared in the jungle near the waters

edge. Several actions happened at once. LT Blair and

his terrified water-gatherers made a dash back into the platoon

harbour. They all wondered who would shoot them first, the

enemy or their own men, as they attempted to rejoin the platoon

inside the safety of the perimeter cord. Sergeant King

meanwhile was endeavouring to control the platoons not

insignificant fire power. By this the time the machine

guns and grenade launchers had joined with the rifles in

sweeping the the platoon frontage. The bush was blue with smoke

, and the bitter taste of cordite hung in the air. Bits of

foliage flew from the vegetation as bullets cut their path into

the ambush zone. This was where SGT King's experience

told. He calmed the soldiers so their firing was directed

and effective. He exerted control over those initial

panicky reactions that are inevitable in a contact. In

minutes it was all over. SGT King took command of the

sweep of the ambush area. Two bodies of Vietcong soldiers,

plus their weapons an d equipment, were recovered. A third

body was discovered some days later by Australian tracker dogs

following up the incident. The platoon had undergone its

first action with the enemy and had emerged safe, sound and

triumphant. Needless to say no one slept very much that

night.

Out of the Line

Denny King discovered early in his tour of duty in Vietnam that

his job was not done once an operation was finished and the

platoon was back in Nui Dat. To the contrary, he found that the

week or so out of the line was a period of more work for him

rather than less. He found that, since the platoon

commander became intensely involved in other duties that he, as

the sergeant, virtually took over day-to-day command. He

held short administrative parades each morning then sent the

sections away under their corporals’ directions to ready

themselves for the next foray. The No 1 Platoon routine

included a complete reissue of ammunition including claymores.

Weapons were taken to the armourer for checking and adjusting

while boots and clothing were also exchanged. He had to

arrange for medical inspections to ensure freedom from infection

(FFI) was maintained. Any reinforcements who had arrived

had to be trained and they spent hours at a time on the range

preparing their weapons and learning the drills.

One of the first events after an operation for W3 was the

company barbeque. After a shower and a change of clothing

for everyone, the company assembled before a quarter-ton trailer

full of ice and beer while the cooks prepared sizzling steaks on

a grill. There was much noise, joshing of those whose

minor misdemeanours made headlines, sharing of jokes and songs

to the standard guitar accompaniment. Revelry might have

lasted well into the night, but the next morning it was parade

again and back to work.

One of the first events after an operation for W3 was the

company barbeque. After a shower and and a change of clothing

for everyone, the company assembled before a quarter-ton trailer

full o f ice and beer while the cooks prepared sizzling steaks

on a grill. There was much noise, joshing of those whose minor

misdemeanours made headlines, sharing of jokes and songs to the

standard guitar accompaniment. Revelry might have lasted well

into the night, but the next morning it was parade again and

back to work.

Occasionally there would be an extended period of leave and

recreation taken at the leave centre in Vung Tau. These

were times when there would be serious mischief, if any

mischief was to occur. The most common offence for 1

Platoon was that a soldier might be late returning to the truck;

he would be charged and might have to serve a field punishment.

Lesser offences might have resulted from some form of frivolous

insubordination or from over-indulgence. Denny King

recalled one such instance involving his soldiers and a senior

Australian warrant officer at Vung Tau.

We

arrived at the Badcoe Club down at Vung Tau. This

Aussie Warrant Officer PTI briefed the boys. He was

dressed in spotless white T-Shirt with a red band around the

neck, ironed white shorts with pockets in them and sandshoes

whiter than a virgin bride. He was an arrogant s.o.b.

and he did not like Kiwis. He gave them the ‘rewles of

the Pewl’ (rules of the Swimming Pool) as if they were

kindergarten kids.

‘No.1. Swimmers must shower before entering the pool.

No.2. Bathers must be worn at all times.

No.3. No swimming after 1900 or before 0800.

No.4. Swimmers must not enter the pool under the influence

of alcohol.

No.5. No bombing off the board or skylarking.’

I just knew, in the light of this provocative talk, that

something was going to happen. It did! That

night…very late…well, after 1900 hours, every Kiwi who came

back to the Peter Badcoe Club, pissed as a chook,

belly-flopped into the swimming pool, fully clothed,

unshowered and swam to the other side before retiring to his

bunk. One actually bombed off the diving board, in the

nude, holding a can of Fosters at midnight! I had to

turn a ‘blind’ eye to all this, because my own vision had

become somewhat blurred by that time.!

So, it seems

that even the strongest glue can come unstuck albeit on the

rarest of occasions. But the inability to supervise late

night swimming activities probably did not come within the scope

of any of the infantry courses completed by Sergeant King that

were devised to prepare him for Vietnam service. If this

NCO was ever to be judged on his overall performance in his role

as Platoon Sergeant 1 Platoon, W3, then the judgements would

rightly have to be made by those who knew him best, his troops.

He trained them, selected them, fed them, armed them, checked

their feet, and cared for them. If they were down he

encouraged them. If they erred he corrected them. He

knew what they needed even before they did. He had been

where they were going and he had done what they were about to

do. He understood. After all, he was the backbone of

the infantry platoon. This combination had been successful

for generations of soldiering and it was no different in the war

in Vietnam.

LT Bill Blair

and SGT Denny King had much in common personally, and they

established a sound and successful working relationship within 1

Platoon, W3 Company, in the ANZAC Battalions. It helped

that both of them were West Coasters. They were delighted

when they discovered that Denny was Hokitika born and bred, and

Bill was a Reefton man. Both their fathers had served in

2NZEF in North Africa and Italy. It turned out that both

had joined the Army as teenagers, had married hometown

girlfriends, and both were determined that their platoon would

be successful.

Bill Blair and Denny met infrequently during their service after

Vietnam. They did not server together again until Bill was

appointed Commanding Officer of Burnham Camp, where Denny was

completing his final year in the Army prior to discharge.

They were, however, invited to make presentations, based on

their experiences in Vietnam to selected groups. During

the 1980's, they travelled to Waiouru for the annual Platoon

Commanders/Platoon Sergeants Courses. Before each

Battalions deployment to East Timor in the early 1990's, they

spent time with each Company's command staff making similar.

On these occasions, they also included George Preston, a former

section commander with 3 Platoon, W3.

Aftermath

Denny King had nothing but praise and gratitude for the Army

after Vietnam. He served on for a full NCO career until

his retiring age for rank and reached all his personal goals.

He attained the rank of Warrant Officer Class I and held the

following appointments:

1978 - 80 RSM, 5th (Wellington, West Coast, Taranaki)

Battalion Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment

1980 - 82 RSM, Army Schools, Waiouru

1982 - 84 RSM, 1st Battalion, Royal New Zealand Infantry

Regiment, Singapore

1984 - 87 RSM, Burnham Military Camp

1986 (Apr-Nov) Training Warrant Officer, Multinational

Force and Observers, (MFO), Sinai

1987 - 90 Senior Instructor, Training Wing, 3 Task Force

Region

1985 - 90 Advisory Warrant Officer, 3 Task Force Region

(dual appointment)

1990 - 94 Warrant Officer (Territorial Force)

Instructor, Training Support Unit

He served as an

NCO on overseas tours of duty to South East Asia four times; to

Malaysia (twice), Singapore (twice), and once to the Middle

East, the Sinai. In New Zealand he was posted to Burnham

four times, Waiouru twice, Blenheim, Wanganui, and Christchurch.

He came to specialise in in the design of training courses for

NCO's in the Regular Force and for Territorials. Denny's

military service was recognised in in 1983 with the award of the

Meritorious Service Medal (MSM) and, again, in 1988 when he was

made a Member of the British Empire (MBE).

When he retired from the Army he was able to extend the training

knowledge that he had acquired in a career spanning 30 years to

his work as a civilian. He established a Training Activity

Centre with two former long serving NCO's, (ex WO1s) Jack Powley

and Manu Lee, and ran special courses under a government

sponsored training scheme for unemployed people. The

company was then contracted by the Army to write the highly

popular and successful Limited Service Volunteer (LSV) training

scheme that the Army conducted for youth volunteers. Denny

King and his colleagues found in the LSV scheme that the

principles they had used to care for, train and discipline their

men in combat were equally relevant to the civilian 'troops'

assigned to the programme. The LSV scheme conducted in

Burnham ran for more than fifteen years, the longest running of

any LSV programme in New Zealand.

Denny ventured more deeply into private enterprise for a couple

of years after the LSV course had been implemented as he and his

wife owned and operated an industrial takeaway in Christchurch.

Finally, for the ten years leading up to his retirement Denny

King was employed as a Training Officer for Canterbury Regional

Council Civil Defence. He was responsible for operational

readiness and providing courses and training for the Regional

and Christchurch City Council staff and volunteers on emergency

management. Denny formed a small Civil Defence Training

Team, comprising mainly former Army officers and NCO's, that

developed courses and conducted training activities for council

staff and community volunteers. They also introduced

regular exercises to simulate situations that could be expected

to happen during a major event. No major events had

occurred in Christchurch since the Waimakariri flooding of the

1950's. However minor events did occur and on those

occasions the Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) was activated

and staffed until the emergency was over. Selected

elements of the Civil Defence were mobilised to provide

assistance and support to Emergency Services and establish and

operate Civil Defence Welfare Centres. As had been done in

Vietnam, where Standard Operating Procedures (SOP's) were

refined from the lessons learned, Civil Defence teams went

through a detailed debrief after each event.

Behind Every Good Man

In his nearly fifty years of working life, both inside and

out of the military, Denny King served in appointments which

required him to provide staunch support for those for whom he

worked. However, he acknowledged that none of that could

have been achieved without the pillars of strength behind him -

the members of his family.

Throughout my career, the support of my wife Jeanette was

magnificent. The nature of a soldier's job means long

periods of separation from the family, and we were no

exception. Jeanette knew, and accepted, that being

married to a soldier was going to be different to most

marriages, and encouraged me to achieve my goals.

Without her support, I would not have been able to devote

the time and effort I needed to qualify on courses, and to

put in the extra hours involved in many of the appointments

I held. Good military wives are exceptional people,

and I was fortunate to love and marry one. I have

always been most grateful for her love, loyalty,

encouragement and advice. My family lived in Singapore

for the duration of Whisky 3 Company's 12 month deployment

in Vietnam. At that stage, we had two pre-school

children. Jeanette and the other wives had no family

support, and relied on friends and neighbours for

assistance. The military support system was available

in the event of any serious situations, but most events the

wives dealt with themselves or with assistance from the

street warden. As with each long separation, my return

was exciting for all, but it brought problems that took time

to resolve. Decisions, purchases, children's

activities etc, had been made without my input, but then I

was back and wanted to be involved again; it was difficult,

but we got there eventually.

Our four children accompanied us on our postings to Malaysia

and Singapore, but the constant moving with postings did

make it difficult for them to establish normal

relationships, to make friends and to get to know their

extended family. They all became very adaptable individuals,

and successful in their adult lives. By 2008 Jane

became a registered nurse and gained 24 years experience in

nursing, including time at Burwood Hospital in the elective

orthopaedic surgical ward. Bruce worked with Gourock New

Zealand for twelve years; he became Manager - Marine,

responsible nation-wide for the manufacture, fitting and

selling of marine equipment for the commercial fishing

industry. Paul served as a regular force infantry

officer in the New Zealand Army, and undertook tours of duty

to Bougainville, East Timor and Afghanistan. Megan, too

established personal links with her fathers old profession.

She served for more than sixteen years in a non-uniform

appointment with the Canterbury Regiment, a Territorial

Force unit based in Burnham, where she became the

Administration Officer.

|