Formal Investigation Ordered During the early afternoon of 10 October Maj Roy Taylor RNZIR [2ic of 2RAR but acting in his capacity as commanding officer of NZ Component] ordered Capt Brown MC RNZIR to formally investigate the 3Pl accident. The terms of reference given Capt Brown required him to report on the circumstances of the accident and those wounded, especially whether the accident was due to any act of misconduct or neglect on the part of any soldiers involved. Capt Brown had until 8 AM 15 October 1970 [only 4-days] to complete the report. Capt Brown visited 3Pl in the Hat Dich twice [on 10 and 11 October] and took statements in the field from five soldiers; Sgt Yandall, Cpl Glendinning, Pte Kenyon, Sig Salt and Pte Lee. Back in Nui Dat he also took statements from Capt Blair RNZIR who formally identified the casualties for the record, and Capt G Hart RAAMC, Registrar at 1AFH who reported on the wounds sustained. In his report Capt Brown wrote a summary to the Investigation where he stated that in his opinion, the ‘incident’ was caused by two things. The first was the misunderstanding by the static group as to the location of the sweeping group. Capt Brown noted that although only very brief orders were issued, Sgt Yandall [like all platoon commanders] relied on his normal communication facilities to coordinate his platoon’s activities, and the equipment failing at a critical time prevented the proper passage of messages and orders. The second point was that since the follow-up had shown strong indications of the possible presence of enemy all members of 2Sect were very alert and under strain to the extent that as soon as movement was seen the normal instinctive reaction was to shoot. Capt Brown stated that in his opinion the accident was not due to any act of misconduct or neglect on the part of any soldiers involved. The investigation was commented on by CO 2RAR before being signed off by a series of more senior commanders and forwarded to New Zealand authorities. As part of this signing off Commander 1ATF officially commented on 3 November 1970 that ‘the clash resulted from a failure in communications at a time when tension was high because of the suspected near presence of the enemy’. In New Zealand Capt Brown’s report disappeared into the Army archives and despite attempts to locate it remained unsighted for 37-years, until in 2007 a different approach from the researcher enabled NZ Archives to locate it. It was then viewed by the researcher under controlled conditions at Burnham Army Camp. Availability of Serviceable Radios Based on evidence presented by Pte Lee, Capt Brown suggested in his report that the matter of testing, maintenance, repair and replacement of radio equipment be examined. Pte Lee had stated that on numerous occasions in the past he had had trouble with the 25-set radios which were on issue to him. A number of times he had asked for a replacement radio set and received one. Several times he had asked for a replacement radio set and not received one because he believed there were none available in working condition. On one occasion he had received a replacement set but on testing found it to be in worse condition than the one he already had. He recollected that prior to leaving for this operation he was told that all of the 25-sets had to be handed in as they were overdue for a check-up and he would get replacements. Shortly afterwards he was told to pack up the present sets for the field and that they would not be checked nor would he get replacement sets. Pte Salt also remembered problems with maintenance, saying that he had had similar trouble with 25-sets on numerous occasions in the past and had to have another set sent to him with the MAINTDEM. He recollected though that this was the first occasion on which he had had trouble with that particular 25-set. Poor availability of radio sets wasn’t only confined to W3 Coy, V5 Coy RNZIR noted in its operational reporting that toward the end of their TOD they were on average experiencing one 25-set failure weekly.

The radio sets used by W3 Coy were hand downs from previous deployments and had probably reached the end of their useful life. That they had not been replaced was most likely due to W3 Coy itself not being replaced in Vietnam. Another issue noted at the time was the issue of a batch of unreliable 25-set batteries. While the 25-set radio batteries would frequently last for 3-days [the normal period between MAINTDEM] late in the W3 Coy tour Maj Torrance recollects that 2RAR received a batch of batteries that quickly proved disappointing, many being exhausted after short periods of time or not providing correct voltage. Operators reacted by carrying spare batteries which themselves might be faulty. Sgt Yandall’s Statement and Other Research In his statement for the official investigation Sgt Yandall made three points that are not supported by other research:

However NCOs from both 1 and 3Sect are adamant that they did not enter the clearing, moving instead around the clearing from the left [clockwise]. It made good tactical sense for Sgt Yandall not to cross the clearing; the clearing was an unsound tactical approach whereas the left approach remained in good cover with tactical options available should they have been fired on by the VC party. This is not to say that Sgt Yandall didn’t intend to sweep from the right and changed his mind when he saw the approach and the researcher accepted that this is the likely course adopted. It might be that Sgt Yandall saw the same ground differently from his NCOs’. Ultimately it is not important what route 3Pl (-) used to reach the dry watercourse. Sgt Yandall also sketched a diagram of where people were located in the area of the dry watercourse as the firing started. However the sketch [which listed names] had the two sections basically in a flat formation at right angles to 2Sect and with both sections jumbled together, and placed Cpl Preston at the opposite end and some distance from Pte Cooper, something Cpl Preston disputes. Given that the sections with Sgt Yandall had been halted for around 10-minutes in an area where VC were thought to be present it is most unlikely that the NCOs’ would not have adopted a defensive perimeter. In fact Sgt Yandall stated to Capt Brown that at that point in his sweep he halted [his] sweeping group and told them to cover all round and go down into a fire position. Sgt Yandall’s diagram has therefore been ignored although the names listed are recorded as being present. [a further observation on the diagram is that the layout of the soldiers may have been affected by having the sketch reproduced in straight lines on a typewriter]. Why would there be this difference from what other witnesses recollect..? The most obvious reason is that the investigation recorded Sgt Yandall’s statement within 18-hours of the accident when he would have been under intense personal and professional stress with his mind on other matters, and he may have had little sleep when he drafted the report. Given the lack of communication within 3Pl following the accident it is also feasible that he actually didn’t know what exactly had happened and chose to offer his original plan as a substitute. By providing an explanation to Capt Brown he was then able to start to move on and resume his role as commander responsible for his remaining soldiers. That the investigation was finished a mere 96-hours after the accident when 3Pl was still in the bush also precluded any opportunity for Sgt Yandall to check detail and it is highly likely that Sgt Yandall never saw the finished investigation. Veterans Health Counselling. In the period following the accident no attempt was made to debrief or counsel the soldiers; but it was not a usual practise in the 1970’s for psychological support to be offered. Section NCOs who briefly spoke to their people recollect the typical response as pure stolid kiwi, ‘she’ll be right boss, don’t worry..!’ In hindsight the troops were in shock, there was little talking among them and they were listless and withdrawn. Pte Newson recollected that they felt disbelief that the accident had happened and avoided talking about it, getting very emotional if they tried. Capt Brown, in a section of the official investigation called ‘Other Relevant Facts’ wrote ‘Although the investigating officer did not take any statements from some of the individuals who were involved with the shooting it is felt that no additional evidence would be forthcoming. In addition, at the time a number of members were suffering from a mild form of delayed shock where detailed questioning and the taking of statements could have further impaired their operational efficiency’. Most amazing is that most soldiers did not discuss the accident even when socialising together, and some still flatly refuse to discuss the events of 10 October 1970 at all. Questions which this research has now answered have always been “why did 2Sect fire on us when they knew we were in front of them..?”, and for 2Sect “why were we not told the others were in front of us..?” . On-going Health Issues. Many of the veterans, Australian and New Zealand, are traumatised by their memories of the accident. They were experienced and hardened soldiers but to their young minds the thought that some of their own were injured in an accident weighs heavily even today. It is the stuff of nightmares, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, poor health. The memories seem more acute today than they were years earlier, exposing as myth a theory advanced by many that those who stayed in the army after Vietnam were less likely to be affected by PTSD than those who left earlier. Many veterans spoken to for this research had remained in uniform after Vietnam and some had risen to high ranks in their profession, but almost all suffer from some form of delayed mental trauma or anguish. Some veterans were in tears when offering their recollections for the research. Similar problems also appear true for the Australians involved; some tracker team members reportedly suffered from depression and alcohol related illnesses, and today are still suspicious of the Kiwi’s motives in wanting to blame the dog [and by inference the handlers] for the accident. Operational Decisions Questioned Decision Making. It is accepted military practise for a commander to ‘plan two down but only direct one down’, meaning the requirement for platoon deployments should have been considered by CO 2RAR but that their actual tasking should have been the responsibility of the two company commanders actually working on the ground. However throughout the period there is evidence of CO 2RAR making decisions on the deployment of individual platoons, removing the initiative from the company commanders.

What was the Prize..? What should have been thought more important, the destruction of a large but vacated VC installation, or the pursuit in strength of the escaping inhabitants..? In late 1970, given the general scarcity of large targets, locating a VC party of 80 – 100 people [a size similar to that of C Coy] should have been treated as a big event with a suitable reaction from senior commanders. When it was obvious that the bunker system found 8 October had just been vacated it would surely have been more useful to insert W3 Coy to take over the destruction of the facility, freeing C Coy already in position to aggressively follow-up and deal with the fleeing occupants. The insertion of 3Pl to the bunker system on 8 October provided this opportunity. Instead the bunker system became a distraction and the search for the missing inhabitants trivialised when the two C Coy platoons were directed to leave their field packs in the C Coy HQ harbour and patrol in opposite directions away from each other, each with a single tracker dog. There seemed to have been an expectation that the VC would simply be located again nearby, but this was always unlikely given the experience and reputation of D445 VC Bn. The decisions to patrol as single platoons and to not carry back packs meant that following their unfortunate contact with the large VC party on the afternoon of 8 October, 8Pl had little choice but to return 1.5 kilometres to C Coy HQ to reclaim their equipment, effectively allowing the VC party an opportunity to escape unhindered. Having failed to aggressively follow-up earlier, the next decision by CO 2RAR to insert W3 Coy [minus 3Pl] into block positions kilometres to the south was always going to be a futile attempt to cut-off well trained VC troops operating on ground of their own choosing. What was the Point..? Using similar thinking to the previous day CO 2RAR again ignored the presence of a large VC party escaping 8Pl by tasking C Coy to stay near the vacated bunker complex. Yet only a formation the size of C Coy with both platoons deployed together had the combat power [being a mix of weapons, intelligence, communications and personnel capabilities] to do serious damage to the large VC party. Assigning the whole tracker team to guide C Coy would also have allowed a faster track as the dogs could have been alternated for rest. Given that 8Pl had failed to overcome 40 VC a day earlier, CO 2RAR’s requirement that 3Pl locate and attempt the same dangerous encounter without further bolstering their combat power seems in appearance more like moving counters on a map than professionally working through appropriate courses of action. In a similar vein is his later requirement that a platoon from W3 Coy return to the original bunker system on 11 October to follow-up long-cold tracks that C Coy had already been tasked to check. His actions beg a question: Was it Lt Col Church's thinking that he had lost confidence in the abilities of C Coy and wanted the more experienced W3 Coy involved in the pursuit..? Involvement of the War Dog

Employment of War Dogs. Australian dog handlers like Peter Haran believe the Australian war

dogs were generally abused by the length of service they were required to complete

before rest. Australian quarantine laws stopped the dogs being repatriated to Australia so ‘it was decided to continue

to employ each dog and allocate them to successive

tracking teams arriving in South Vietnam until the dogs tracking skills became somewhat diminished for whatever reason’.

Milo arrived with 4RAR in 1968, was transferred to 6RAR in 1969 and then passed to 2RAR in May 1970, three tours of

duty in a climate described as naturally unhealthy for dogs but with the added issues of injuries sustained in contacts and

accidents. There are reports on the internet of war dogs in Vietnam suffering from shellshock, loss of hearing, limb damage and several internal parasite infections. It is likely that in

October 1970 for health reasons neither Marcus nor Milo was properly fit for duty. It is also obvious by

the lack of backup given the dog handlers that the tracker dogs were being employed in a ‘police’ tracking role [i.e. where no

one is likely to shoot back if you got too close] instead of an active The courage of the war dog handlers and visual trackers therefore needs mention, because they knowingly walked into dangerous scenarios in violation of the proven principles of close-country warfare, and frequently did so without adequate backup from escorting troops who were working under conditions they normally did their best to avoid. Conversely, thrusting a tracker dog and handler into a rifle platoon was guaranteed to disrupt the smooth operation and well practised drills any rifle platoon relied on to survive. Both organisations were seeking to locate the enemy before contact was established but by fundamentally opposing means which disrupted the other. Lt John Alcock [platoon commander 2RAR tracker dog team] offered this comment: "I guess we trained the teams but neglected to train the various Command levels we supported on how they were to be employed. A tracking team should not be employed, particularly in a SVN environment, with only one dog and without other team members who are trained to cover and support the dog and handler. I really feel for Ron Johnson and John Hobbin and poor old Milo who incidentally was a great tracking dog. Tracking enemy is an extremely stressful task and requires a lot of faith in your dog, it helps to know you have team members who know their job and are covering your arse.” Difference between Patrolling and Tracking. Maj Torrance commented: “I was very angry that I had failed the Company and 3Pl in particular in letting operational direction slip out of our hands.” What was the operational direction referred to..? There is a large difference between patrolling and tracking. W3 Coy was very good at patrolling, using combat proven principles such as not walking on tracks [to avoid ambushes and mines], moving on compass bearings across terrain [to assist accurate location and to approach suspect locations from an unexpected direction], and close reconnaissance of likely targets [to prepare the best assault plan possible]. Tracking violates the character of operational patrolling by failing to observe any of the proven principles:

In appearance Sgt Yandall’s decision to alter his deployment can be seen as attempting to overcome these three factors, in the process wresting back the initiative both from the VC he was pursuing and from the limitations imposed by the tracking process:

It is obvious that given his preparations Sgt Yandall rightly backed his troop’s skills and abilities against those of the VC force. Later changes to his plan, such as the intended approach proving to be tactically unsound, would have normally been announced by radio and the plan altered safely. And had 3Pl actually contacted the VC force the loss of his personal radio would have been hugely compensated for by the earlier preparations. Was there VC in front of 3Pl..? Given the physical sign observed by 3Pl it has to be accepted that a party of VC were being tracked by Milo on 10 October 1970. The initial sign was probably 36-hours old when the track started but there were indications that the VC party were hampered by wounded and may have been travelling slowly. Frequent stops [as would be required if wounded were being carried by litter] would have caused the scent to concentrate and Milo would have reacted to the increased scent by indicating as he was trained to do. The Australian Tracker Platoon people interviewed for the research spoke highly of Milo as a competent tracking dog and they accept that the track was genuine. [Lt Alcock: “I have little doubt that each time Milo pointed, the enemy was close by, or had rested at that location allowing the scent to build."] [Pte Matusch: “great dog, great heart, good tracker”]. Other 3Pl soldiers also recollect the track as they followed it although at times, where the scent may have drifted to one side it is probable that there would be little physical indication of the VC party movement. Was animosity shown the Australian dog after the accident..? Undoubtedly true, an example is Sgt Yandall offering 'to shoot the bloody dog' while waiting with Pte Dunlea on the pad prior to the Dustoff. Even if this sentiment was passed to the tracker team as bluster it can be imagined that the team members would have felt very defensive and concerned. BUT today most veterans spoken to are in agreement that the dog did not cause the accident, offering instead the [generalised] statement that Milo’s constant pointing ‘revved’ up their adrenalin which may have made them over-responsive to other stimuli. Cpl Preston for example recollects being unhappy about the manner in which the dog was used but states that the dog was ‘just doing its job’. These animals and their handlers have earned the right to have their service afforded the same courtesy and care of memory expected by all other veterans. Communications 3Pl Internal Communications. It is obvious from the recollections that verbal communication within 3Pl was minimal, but this was not unusual. 3Pl soldiers had worked together for many months [about 300 days on patrol in Vietnam and about 75 days during pre-deployment training in Malaysia] and ‘knew’ what others were doing and thinking because of their shared experiences. A lack of formal orders due to urgency did not mean a lack of other communications such as hand signals and gestures or whispered messages that were passed from man to man along the patrol file; and reacting quickly under urgency [such as a contact front] was drilled into soldiers so that their reactions were effective and timely. However, given the familiarity of their shared service it is possible that assumptions were made by some people that later impacted on others. These assumptions might have been that individuals knew something when in fact they did not [in effect like Chinese whispers], so that later actions were ordered on the basis that everyone knew about earlier decisions when they didn’t. While making such assumptions would have been unprofessional they were also a fact of life in a close environment where few soldiers saw more than their immediate neighbours during any all-day patrol. An example of this is in the individual bush skills where despite being only 50 or less metres apart neither element [about 30 people in total] heard the other even when one or other element was moving about. There would also have been an expectation that questions would be answered by means of functioning radios, so the unfortunate loss of effective communications meant that those making decisions were required to remember Sgt Yandall’s intentions as portrayed by him at the brief orders groups 30-minutes or so prior. 3Pl

Radio Communications. On 10 October 1970

it is likely that every technical and operational difficulty a field radio operator could face on active service was being

experienced by the two 3Pl radio operators. Having two platoon radios should have ensured good communications between

the two commanders and back to supporting arms but the difficulty of using in close-country a low-powered model of radio that

required line-of-sight to operate properly meant that there were many technical difficulties to overcome. From their

actions and the deployments of their radio sets it is clear that both Sgt Yandall and Cpl Glendinning had these issues on

their minds late morning 10 October 1970. Throughout the war diaries over this period there are numerous entries

concerning poor radio communications, such as frequency clashes with more powerful US radios some distance away, heavy jungle

canopy smothering the carrier wave, and physical issues with the radio sets and their batteries. Under operational conditions

these issues could not be dealt with easily. Arranging for a frequency change required approval and coordination at unit

or higher level if all radios were to change their

frequency at the same time or face being cut-off completely. Ironically, even establishing the cause of a frequency clash required reasonable communications which was difficult for operators on the move and in close proximity to the enemy. Operators had to maintain ground and communication security while trying

to influence their position to improve reception. In an unfolding tactical environment the radio operator would be required to conform to the other platoon elements

that might be quickly moving and would for a time need to cease communicating, especially if the operator needed to remove a

rigid 10’ aerial he had been using to improve reception. Operational requirements meant that when close to the enemy the radio operator was not allowed to talk properly and resorting to the ‘break squelch’ method

was normal for security. Other restrictions were commonplace, such as not showing lights at night so m Sometimes the issues were at the transmitting end of the ‘message’, at other times the receiving station had the issues. Most radio operators tried ‘tricks of the trade’ to off-set operational parameters and achieve workable communications but in difficult circumstances both ends of the message needed to be effective if the traffic was to be passed at all. These issues were sometimes overcome by having other call signs monitoring for messages and relaying these where able, or by changing to another [sometimes unauthorised] frequency. A Garbled Message. There were several references in the official investigation to messages between c/s53A and c/s53 being garbled, meaning that the message was received in a truncated form where only parts of the message were clear. Normally an operator would request the transmitting call sign to ‘say again, over’ but when elements were in close proximity to VC this procedure was officially discouraged or the request simply ignored. Complicating the issue is the operator being required to accurately repeat what was received [in this case ‘to move forward’] and the local commander needing to fit this scant information into what he believes his next move to be [to advance against the second VC position]. It can be accepted that this dilemma contributed to the accident. Other Operational Decisions Choice of Private Soldier to Command 2Sect. Pte Bill [Pancho] Kenyon the 2Sect 2ic became section commander in Cpl Glendinning’s absence; he was considered the best private soldier in the platoon and based on his performance as Section 2ic deserved the appointment. Maj Torrance recalls “All reports that I received indicated that ‘Pancho’ was a very capable Section 2ic … his ‘leadership training’ was on the job on active service”. If Sgt Yandall had chosen, another NCO could have been reassigned to command 2Sect in place of Pte Kenyon, but it was not unusual to want to keep experienced tactical teams together. Should a Private soldier have commanded a rifle section..? Maj Torrance observed “Our establishment did not allow us to have all Section 2ic posts filled by NCOs. My manning chart shows that towards the end of our tour, of the nine section 2ic slots only four were filled by NCOs. It is my opinion that Pte Kenyon was probably at that stage of our tour one of the most experienced Section 2ics in the Company and Sgt Yandall would have been happy with the arrangement.” Contact Front Immediate Action Drill. The accident started with 2Sect initiating a ‘contact front’ immediate action [IA] drill. The IA required the soldiers to immediately engage the area within their arcs with a heavy volume of rifle and machine-gun fire. During the IA it was not important for the soldiers to see a target before firing at it, rather what was wanted was a huge volume of fire to suppress the enemy thereby allowing 3Pl the initiative to more safely move and dominate the encounter. The drill typically required the machine-gunner to fire a full belt of 200-rounds into the contact area, with individual riflemen each emptying a magazine of 20-rounds. Once this initial part of the IA was over and there was a lull in the firing while soldiers reloaded, the section commander was expected to assume control, issue a specific fire order, and start to deploy his soldiers to better dominate the VC. In the circumstances of the accident 2Sect had not finished their initial suppressive fire phase before various people started to realise what was happening and responded quickly to stop it, something only fully professional and very experienced soldiers would have been able to do. It can be accepted that the casualty count was lower because of this factor [and the fortunate jamming of the 2Sect machine gun]. Questions Answered by the Research An historical researcher is required to gather facts, give each fact a weighting and then responsibly assemble the facts in a way that provides interested parties with an answer. In researching the 3Pl accident against the fabric of the Vietnam War in general and the New Zealand contribution to 1ATF the researcher sought to answer three other distinct questions: 1.

Was a crime committed..? Was a crime committed..? The Vietnam War was controversial for many reasons, among which are stories of massacres, ‘fragging’ of unpopular commanders, and accidental deaths caused by unauthorised discharges of weapons. Was a crime committed on 10 October 1970..? The answer is NO. No member of 3Pl wished to harm another comrade alongside whom they had toiled for 300 odd days of tough bush warfare. Is there a secret hidden in the facts..? Is there some detail in the research which shows that something was concealed from public view..? The answer is NO. The accident was quickly identified as an accident and reported as such as soon as practicable. Full disclosure was made back to Army HQ, the details were released to the media, and an official investigation was conducted. Inconsistencies in the record can be explained as typical for the environment and do not constitute a cover-up. Were there special circumstances which need explanation..? The answer to this question is YES. This accident happened to soldiers living on the edge of reality in a tough quest to dominate the jungle. They had been ordered to deliberately go into harms way, and they had willingly submitted to the disciplines and restrictions required for this domination to be effective. AND they had cared for each other from before they deployed from Malaysia right through their operational tour of duty, and continue to do so today. Within W3 Coy and especially 3Pl each person demonstrated a willing professionalism to shoulder responsibility for seeing through a deadly act of war under whatever circumstances they encountered. They had not degraded themselves into sub-humans uncaring about human life. They had not attempted to escape the danger and toil by giving in to drugs and other crimes. They were honest toilers and very successful professional soldiers. By a slight edge 3Pl had the highest VC body count of all the W3 Coy platoons. In a sense the accident happened because of their professional standards, YET the death and injury toll was also very small because of their personal skills. What other special circumstance needs explanation..? The worst consequence of this accident has been the way some soldiers [including the dog team] have assumed for themselves or had thrust upon them, responsibility for the fact that the accident happened at all. This accident had basically been avoided every other day that they had patrolled in Vietnam. The research shows that the accident happened because a number of more minor happenings led to a situation where the accident was practically unavoidable. Things like having no experience or training to work with tracker dogs. Things like expecting to find VC in the vicinity and anticipating the encounter over and over as they advanced along a known enemy track toward a very competent enemy. Things like the lack of reliable radio communications throughout the preceding days and the loss of communications at a crucial moment. Who can be held responsible for what happened..? CO 2RAR for ordering 3Pl to operate under similar circumstances to 8Pl..? Maj Torrance for not requesting Milo be removed..? Sgt Yandall for separating 3Pl into two groups..? The dog handlers for their interpretation of Milo’s body language..? The radio operators for faulty equipment..? The minimal formal communication within 3Pl, especially within 2Sect..? The failure to promote a private soldier before he assumed command of his friends in what is called a ‘battle-field promotion’..? Realistically no one action caused the accident, and realistically no one person can be called to account for the outcome, even if for some reason they wanted to. The accident that happened to 3Pl W3 Coy on 10 October 1970 is a tragedy which lingers to this day, and which affected more that the four injured soldiers. It would be perfect if it had not happened, but considering casually such events like the friendly fire from C Coy at the water point on 8 October, it is perhaps even more remarkable that an accident like this did not happen more often. Ultimately it was the skill of the 3Pl soldiers that avoided a far worse result; they deserve to be commended for their professionalism and thanked for their service. Part 5: Events 11 - 14 October and Casualties <<<< >>>> Index to other parts of research The detail of the 3Pl accident as published on this website is the only authoritative record of the accident and any earlier version of the research which was on limited distribution to W3 and other veterans needs to be destroyed. If a written copy of the research is desired the version finalised in time for the rededication of Tom Cooper's headstone in January 2008 is available here. However this website record is still an active research project and will be updated when further details are discovered. |

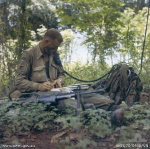

![Pte Ron Johnsom & Milo [Wardog archives]](images/Johno_Milo.jpg) service role [i.e. where someone was very willing to

shoot back], in the latter the handler needed dedicated backup right on his elbow watching the bush for what the handler

couldn’t see if he was to watch for and interpret changes in the

dog body language. In an unrelated email,

Australian visual tracker

service role [i.e. where someone was very willing to

shoot back], in the latter the handler needed dedicated backup right on his elbow watching the bush for what the handler

couldn’t see if he was to watch for and interpret changes in the

dog body language. In an unrelated email,

Australian visual tracker